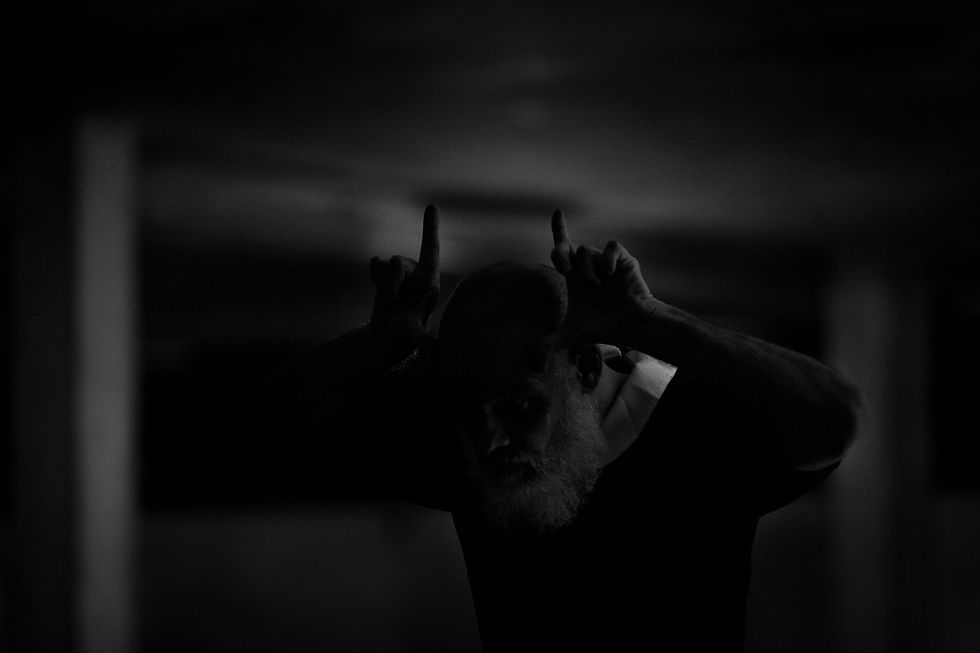

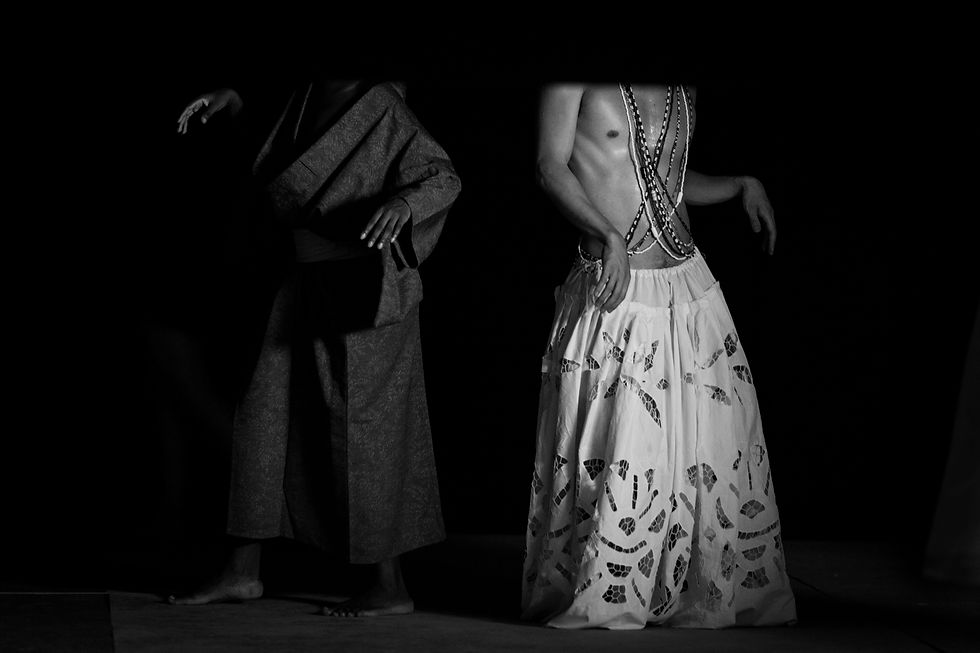

What might dance mean for tired, fragile and suffering bodies? Marcelo Evelin and his company Demolition Inc. offer raw, head-on experiences that reveal the dark side of life and break with the certainties of contemporary dance. After a career spanning more than thirty years, the Brazilian choreographer has also focused on the body’s physical decline. Dança Doente (“Sick Dance”) stages a body that is infected by the world and dominated by external forces that are wearing it out to the point of ruin. Marcelo Evelin found his inspiration in Hijikata Tatsumi, the pioneer of butoh, also known as the “dance of darkness”, created in Japan in the 1960s. Approaching dance as the material of a molecular symptomatology, the pathology of a moving body, he rendered it viral, contagious, post-apocalyptic: the omen of certain death, brandished to reaffirm the power of life. Essential viewing!

Que peut signifier la danse pour des corps fatigués, fragiles, souffrants ? Marcelo Evelin et sa compagnie Demolition Inc. offrent des expériences brutes, frontales, qui montrent la face sombre de la vie et rompent avec les certitudes de la danse contemporaine. Après plus de trente ans de carrière, le chorégraphe brésilien a aussi développé une attention pour la déchéance physique du corps. Dança Doente (« danse malade ») met en scène un corps infecté par le monde et dominé par des forces externes qui l'épuisent jusqu’à la ruine. Marcelo Evelin a trouvé son inspiration chez Hijikata Tatsumi, pionnier du Butoh, la « danse du corps obscur » née au Japon dans les années 1960. Approchant la danse comme la matière d’une symptomatologie moléculaire, la pathologie d’un corps en mouvement, il la rend virale, contagieuse, post-apocalyptique : le présage d’une mort certaine, brandi pour mieux réaffirmer la vie dans toute sa puissance. Essentiel !

Wat kan de dans nog betekenen wanneer de lichamen moe, breekbaar en noodlijdend worden? Marcelo Evelin en zijn gezelschap zijn bekend van rauwe, frontale dans- ervaringen die de schaduwkant van het leven tonen en breken met de veilige tradities van de hedendaagse dans. Na meer dan dertig jaar in de dans groeide bij de Braziliaanse choreograaf echter ook een bezorgdheid over het fysieke aftakelen van het lichaam. Dança Doente (‘Zieke dans’) benadert de dans als pathos, als een symptoom van een lichaam dat door de wereld geïnfecteerd is en gedomineerd wordt door externe krachten die het opgebruiken en dumpen. Inspiratie zocht en vond Marcelo Evelin bij Hijikata Tatsumi, een pionier van de Japanse schimmendans butoh in de jaren 60. Het stuk organiseert zichzelf, als een gedanste pathologie, een organisme van lichamen die uit en in zichzelf bewegen. De dans is postapocalyptisch: als een besmettelijk virus, een voorbode van een gewisse dood, maar enkel om het leven in al zijn kracht te bevestigen. Het is kunst over de essentie van ons bestaan.

Premiere

may 2017

Kunstenfestivaldesarts

Brussels - Belgium

A piece by

Marcelo Evelin/Demolition Incorporada

Concept and Choreography

Marcelo Evelin

Creation and Dance

Andrez Lean Ghizze

Bruno Moreno

Carolina Mendonça

Fabien Marcil

Hitomi Nagasu

Marcelo Evelin

Márcio Nonato

Rosângela Sulidade

Sho Takiguchi

Dramaturgy

Carolina Mendonça

Artistical collaboration

Loes Van der Pligt

Space

Marcelo Evelin and Thomas Walgrave

Light

Thomas Walgrave

Sound

Sho Takiguchi

Technical direction

Luana Gouveia

Research Advice

Christine Greiner

Costume advice

Julio Barga

Training Traditional Japanese Dance

Heki Atsushi

Voice in off

Ohno Yoshito

Photography

Mauricio Pokemon

Video

Jose huedo

Mauricio Pokemon

Production direction

Materiais Diversos +

Regina Veloso/Demolition Incorporada

Agency and distribution

Sofia Matos/Materiais Diversos | Abroad

CAMPO | Brazil

Co-productions

Brazilian Government/ This project was awarded by Prêmio Funarte de Dança Klauss Vianna 2015

Kunsten Festival des Arts, Brussels (BE) NXTSTP

Teatro Municipal do Porto - Rivoli - Campo Alegre, Porto (PT)

Festival d'Automne à Paris (FR)

Kyoto Experiment KEX (JP)

Spring Festival, Utrecht (NL)

HAU Hebbel Am Ufer/Tanzimaugust, Berlin (DE)

Teatro Municipal Maria Matos with Alkantara, Lisbon (PT)

Montpellier Danse, Montpellier (FR)

Mousounturm, Frankfurt (DE)

Goteborg Festival (SE)

TanzHaus, Dusseldorf (DE)

Vooruit, Gent (BE) | NXTSTP (with the support of the EU Culture Programme)

In Residency at

Teatro Municipal do Porto/Rivoli - Campo Alegre, Porto (PT)

Mousounturm, Frankfurt (DE)

CAMPO | gestão e criação em arte contemporânea, Teresina-Piauí (BR)

PACT Zolverein, Essen (DE)

Vooruit, Gent (BE)

Studios C de La B, Gent (BE)

When life empties itself into movement

Christine Greiner

Western artists began showing great interest in butoh dance in the 1980s. The performances of Kazuo and Yoshito Ohno were particularly inspirational and paved the way for other Japanese artists such as Ko Murobushi, Ushio Amagatsu, Anzu Furukawa and Carlotta Ikeda, who over the next decade or so started performing and training dancers in Europe and America.

The name Tatsumi Hijikata came out of the shadows. Hijikata actually never left Japan and after his death in 1986 it took some years for his research to eventually come to light. Films, programmes and photographs had been archived somewhat haphazardly in the small Asbestos kan studio where Hijikata and Akiko Motofuji lived and worked from the 1960s, while other works had been distributed among his disciples and friends.

All that changed in 1998 when the Hijikata Tatsumi Archive was created at Keio University in Tokyo and the publishing house Kawade Shobo Shinsha published the first edition of his complete works (Hijikata Tatsumi Zenshû) in two volumes.

In the end, a large proportion of his choreographies and research material were made accessible to the public for consultation in situ at Keio University or via the internet thanks to the digitalisation of several images.

Of these documents, the sixteen notebooks on his creations that constituted what is known as the butoh-fu notation system and the book Yameru Maihime (The Sick Dancer) have turned out to be particular enigmatic. The notebooks included newspaper cuttings with paintings and photographs by artists he admired such as Goya, Klimt, Wolz, Bellmer, Picasso and Bacon. They also contained notes and diagrams. Although interpreted as studies that were intended to develop a specific method of creation in dance, these notebooks were more like a personal diary of an artist without concerns, full of instructive explanations. These projects, which were designed to systematise and decipher gestures, metaphors, instructions and norms of movement, were largely linked to the endeavours of his best students and dancers, such as Yukio Waguri, Moe Yamamoto and Kayo Mikami who developed methodologies for teaching butoh.

As for the book Yameru Maihime, Hijikata’s last work, it can be defined as an anti-autobiography since strictly speaking it does not deal with stories or events from the past. Rather it is a work constructed from a stream of perceptions about his homeland and his reflections on a tired body. There is an unexpected rhythm to it and an inexpressible link between what is said in it and who says it, with no clear separation between the writer and events. A chaotic movement is created, with several shifts in phase between gestures and voice, with Hijikata remaining in the text while drastically changing the usual grammar of words and the same anti-method of his dances through movements.

As far as I am aware, this book has never been published in full in a western language, but it has been disseminated in quotations that have been translated by researchers and artists interested in his work.

Butoh in Brazil

There has always been considerable interest in butoh in Latin America, particularly in Brazil, Argentina and Mexico. The first tour to the continent by Kazuo and Yoshito Ohno was in 1986 and it triggered a whole series of experiences that were initially coloured with exoticism, fetishism and personal development.

Other possibilities subsequently opened up, with the publication in Portuguese of essays by the philosopher Kuniichi Uno (A Gênese de um Corpo Desconhecido - The Genesis of an Unknown Body, 2012) being based on experiences that endeavoured to identify a kind of butoh thinking and its philosophical power based on singular ways of seeing the body and territorial spaces.

It is in this experimental setting that the work of the Brazilian choreographer Marcelo Evelin can be positioned.

Starting with a politico-existential style, Marcelo immersed himself in the remains he discovered of Hijikata’s work, always searching beyond a technical or exotic cultural context. As I see it, it is Hijikata’s ghost that has come to haunt him as an opportunity to deal with radical destabilisations by constructing a philosophy of life that, in trying to survive on the basis of a sickly dance, leads him to extreme exposure of the body.

Thus it is not about adapting or learning a specific physical training. There is no relationship either with the imagination of transcendental butoh, as has been studied by other artists.

The movements constructed by Marcelo do not leave any room for ready identities, supposed aesthetic models and even less so for a fetishism of stereotypes. What is indicated by his research reinforces questions pertaining to sexuality, ritualization and echoes of voices and movements. Thus it is not about a discourse, but about the corrosion of bodies through words, images and feelings. And more than a model of cultural hybridisation, what is visible are the frictions running through it while symbolic representations, whether they come from Japan or Brazil, are resisted.

Starting points for a “Dança Doente” (Sick Dance)

It is important to note that although he comes from Brazil, Marcelo has always conducted his research by being intensely nomadic. As a dancer, his training came from cohabiting with foreign artists such as John Murphy in New York, with whom he created his company Demolition Incorporada in 1995, and with leading names on the European scene such as Odile Duboc, Pina Bausch, Mark Tompkins, Lila Green and Arthur Rosenfeld, with whom he studied and worked for the twenty years he spent outside Brazil. His partnership with the Netherlands has been particularly significant and continues to this day as Marcelo still teaches at the Mime School of the Amsterdam University of the Arts.

This restless and dynamic stance has never pushed him to create dance companies or groups in a conventional way, as so often happens, but rather to develop platforms of creation and sharing, as has been the case with his company Demolition Inc. and Núcleo do Dirceu which he coordinated with young artists (mainly from Teresina) between 2006 and 2015 in the district of Dirceu.

In the specific case of Dança Doente, initial outlines for the project were based on a recognition of what north-east Brazil and north-east Japan have in common, more specifically Teresina (capital of Piauí) where Marcelo was born and Akita (Tōhoku) where Hijikata was born. These two places share an extreme climate (unbearable summers and winters) and being stigmatised by their distance from large economic hubs and centres of tourism.

However the discussion does not just revolve around geopolitical matters. For example it could be speculated that this research began, without it being called as such, during the creation of the trilogy Os Sertões (Rebellion in the Backlands) by Euclides da Cunha, one of the great classics of Brazilian literature. Indeed, to choreograph Sertão (2003), Bull Dancing (2006) and Matadouro (2010), Marcelo had already started studying the bridges between writing and the body, the earth and the harshness of life.

In Mono (2008), which was created between these works, there was already an explicit reference to Hijikata, considered in this context as a kind of virtual mentor for dealing with issues of sexuality and gender using the manipulation of dolls. This could also suggest a confrontation of tensions between the animate body and the inanimate body, between subject and object.

In 2011, Marcelo was invited by the curator Yusuke Hashimoto to take part in the Kyoto Experiment festival with his work Matadouro (2010). This invitation, which has been repeated in subsequent years, opened up new areas of research. It also offered the concrete possibility of coming into contact with some of the primary sources of Hijikata’s work archived in Keio University and ending up in north-east Japan. Over several months he collected statements from critics, researchers and artists about Hijikata, butoh and north-east Japan. They included the dance critic Kazuko Kuniyoshi, the curator of the Hijikata archives Takashi Morishita, dancers Yoshito Ohno and Setsuko Yamada, and Kuniichi Uno in person.

Their testimonies have without doubt been fundamental, along with his study of pictures and a trip to Akita, were he ended up being able to feel for himself the brutal cold that goes right through to your bones, the abandonment of the region, the belated reverence for an artist who for a long time was ignored as a kind of accursed artist, but who is increasingly being remembered not only on the contemporary art circuit, but by the elderly inhabitants of Tōhoku who regularly meet to study his book.

It is important to note that Marcelo has actually never managed to read Yameru Maihime because it has not been translated. However this has not stopped him from feeling in his flesh the sickness of death – the very one that has afflicted so many other artists such as Marguerite Duras, Clarice Lispector, Antonin Artaud and Vaslav Nijinsky.

There is a power in this exposure to death that reverberates beyond Hijikata, Brazil and Japan, in the territorial spaces of bodies that experience the risk of living without concession on the edge of the abyss.

Perhaps this is about the vitality of butoh, shifted away from itself and from its historical contexts, but still able to help us face the scarcity heralded in this age of radical neoliberalism.

Christine Greiner is a professor at the Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo. She is the author of Leituras do Corpo no Japão e suas diásporas cognitivas (Lectures on the Body in Japan and its Cognitive Diasporas) (2015) and Corpo em crise (The Body in Crisis) (2010) among other works published in Brazil and abroad. She has also translated Kuniichi Uno’s books into Portuguese.

foto por Mauricio Pokemon

Publicity photos

Publicity photos

Publicity photos

fotos por Mauricio Pokemon

Critiques

May 11, 2017

Photos about process

fotos por Mauricio Pokemon

Photos backstage Spring Festival

fotos por Anna van Kooij

Interview conducted via Skype on December 7th, 2016.

Carolina Mendonça: I thought we'd start with a very open question. In general terms, what is this new work? Or how did the idea of Dança Doente (Sick Dance) come about?

Marcelo Evelin: Dança Doente (Sick Dance) came from sort of a fascination with the universe of Hijikata Tatsumi, the Japanese choreographer who created the Butoh dance form. Since 2008, images of him and his aesthetic propositions have been roaming through my work, but when I started going to Japan in 2011, these images began resonating more strongly with my universe and to a lot of my questions as a choreographer, as an artist…Sick Dance has been developing from there with the two crucial questions that are in the title. The first is the idea of Dance. What is dance today? What can we do with dance? How can we think of dance as the activation of a corporal state which leads to a state of common[CN1] ? Dance as a type of standpoint that is determinant in the political and artistic conjuncture of the world. This is a question that was always strongly brought up by Hijikata, we he tried to formulate a dance that was specific to his standpoint. I think his insistence with the idea of dance brought forward my insistence and my questions, as well as an enormous desire to create a dance piece, questioning, in this piece, exactly what dance has always meant to me.

The other question is the idea of sickness. The “sick” in the title comes from Hijikata's last work, which is this book called “Ailing Dancer”. A book I have never been able to read because there is no translation, but that I can imagine from what I hear. It’s almost a danced autobiography, a book where he resorts to images of childhood, adolescence, of how everything began building up for him; he goes back to all the questions which guided his work during thirty years. From the book I got this idea of an ailment, which is also very present in his works, and started putting it all together, asking myself how we could understand dance as a Symptom. The symptom is exactly that moment where the body alters and shifts its perception of itself. A subjective description of a condition by the body itself. There is a difference between symptom and diagnosis. The diagnosis is what the doctor, through his technique, is able to assess and give a name to. The symptom is a shift, a subtle altering of the perception in your own body, of your own existence, and can only be described by the patient.

So, Sick Dance is a piece that's being built around these questions.

C: Listening to you, it seems like the relationship you establish with Hijikata's universe, and with the dance itself, has less to do with the form and more so with an investigation of what dance is as language.

M: One of Hijikata's propositions that interests me the most, which was one of the first questions to come up in this process, is the idea of separating the body from language. This still is incisive in the piece, almost an impossible question to face, and this side of it also interests me. What I feel Hijikata has done is exactly not considering dance as a form, but mainly as a process of transformation of a corporal, psychic, emotional, mental state… This constant process of transformation is one element I consider very important in dance. I see dance as a process of dissolution of rigidness, as something more fluid that somehow determines the bodies continuously, along with the friction of these bodies with other bodies, with the world, with the questions that permeate all of this. Lately, I think of language as something outside of itself, as the dismantling of language. Again, as transformation, precisely to take itself elsewhere.

C: We are talking about these issues that are your starting points, and I wanted to understand how they transfer to the rehearsal room. Take us through your creative process.

M: My process is always very intuitive and looks like a chase. It's always the process of pursuing what has not yet vanished, what remains, insists, comes back. I have a process of seeking something that is unclear, that changes when I approach it. In this piece, it's almost as if we're chasing the idea of a spectrum, a ghost. The play has something of phantasmagoria to it, which to me is key to its intentions, the laws and rules that permeate and structure it. So this process is the pursuit of something that doesn’t exist, or exists no longer, or maybe never existed at all.

In the case of this creation, I had a longer process than I normally have before starting rehearsals. I spent two years on the verge of starting, constantly preparing, and things kept changing all the time. All the ideas I had for the process, of starting with one question, one image, all of those keep dissolving, keep transforming, or I lost them. To me, the research I did now in Japan was very much a process of not gathering more material, elements and ideas about Hijikata, but instead killing the ideas I already had. A whole investigation based on losing all the references I previously had or making banal the more didactic ones that could help me build a piece. Relativize, abandon, lose all of it. Therefore, the most important thing I have now is: how to position myself in a place where I can let myself be traversed by an uncoded language. How does my body, my dance, position itself towards something that traverses, that intercepts, that makes use of this body. As if we were one of those airport windsocks, placed there to tell where the wind is coming from and where it is going.

C: Yes, with this idea of a ghost, an apparition, it seems like this dance is less an action than a way of listening.

M: A perception...

C: Or another understanding of dance...

M: It is hard to tell, because it seems pretentious for me to say that it is another kind of dance, it seems like we’re inventing something that doesn’t already exist. But I feel that, yes, it has a lot more to do with amplifying a perception, activating a kind of absolute corporeal consciousness, happening in time and space, so to me, it is dance. I have demanded a high rigor of dancing in regards to the perception one has of oneself, with the permissiveness of this corporeal state. More than the construction of a body, of a corporeal language of movements and gestures, I think of it as altering and amplifying consciousness.

C: You spoke a lot about the idea of ailment as transformation, and I feel like the piece also has the idea of Death as one of its apparitions...

M: I feel the state of sickness in this piece has to do with this complete destabilizing of the body and all the processes that keep the body alive. Death is almost the flip side of an enormous potency for life. It is the other side but also it's life's siamese twin sister. Intuitively, I feel that the potency for life is very close to an absolute state of death. What fascinates me in death is this idea of utterness[CN2] , death is death, something we know is going to happen and is absolutely determinant in our life. The question would be: how can we exist in life with decisiveness, with the magnitude that we're going to exist in death?

I usually think that dead people live inside of us, and Hijikata's dance was wholly permeated by this, as he said he spent his entire life dancing with his dead sister inside his body. So he spent his life feeding a dead sister, a dead body, and I think it gave enormous potency to his life. This whole idea of haunting, of ghosts, the Japanese conception of it is that it comes through a kind of sensation, a vibration in the air, that they call kehai. The idea of spectre is very important to me in this process, but not in the western comprehension, of a ghost that is related to a personality. Kehai establishes itself in space and comes as a situation that occurred, a tremor in the air. Didi-Huberman speaks a lot of the unfolding of images and the apparitions that are created as these images unfold. I don't know exactly how to go into that, but I am rather curious, almost as a technical element of this research, to unfold Hijikata's images, not in the sense of making them visible, but to create space for the spectre in those images that ravage me somehow.

C: I thought about the relation to the Kinjiki (Forbidden Colors), in that there’s no attempt of necessarily remaking or reassembling his performance, but instead almost letting him disappear.

M: Yes, it's much more the spectre of the Kinjiki than a reconstruction or homage. It's more about what remains, what haunts me when I see Ohno Yoshito in the kitchen of his home making a gesture from a dance he performed 57 years ago. I like to think of Dança Doente as a parenthesis between the Kinjiki (Forbidden Colors - 1959) and Yameru Maihime (Ailing Dancer - 1984), Hijikata's first and last works. The Kinjiki as an initial mark, a near provocation, Hijikata's drawing attention to his dance; and Yameru Maihime, a book no one is able to translate, with its bifurcated writing, ambiguous, destabilizing the construction of sense, creating a much more sensorial reading.

C: The work is very strongly related to Japan. I wonder what thoughts you have regarding Brazil.

M: My last research trip to Japan consisted of killing all the references, unmaking all the clues I had. Setsuko Yamada, a Japanese choreographer, was very emphatic when she told me that “your research is not necessarily Hijikata. You have to find your Hijikata elsewhere. What Hijikata perceived as Dance, as a concept, is not directly linked to Japan, to kimonos, to Tohoku.” She directly said, “Your Butoh, your dance, is in Brazil”. More and more, I began recognizing, during the process of the residencies, the presence of Candomble and the Macumba traversing the process. I am trying to open my perception specifically towards the processes involving the ideas of Incorporation, of Traversing, of Mediumship, of other forces and other worlds coming through bodies and celebrating with dance, like in Candomble. The idea of a Ritual is also present in Hijikata's work, but in a non-solemn manner, it is completely mundane and irreverent. I am finding those approaches, but it's hard to tell how much we're going to go into that. It's something that is permeating the process right now, like crossing distinct references from the same world.

C: From the start, we experimented with a spatial conception that directly informs the audience of the material being produced in rehearsals. What is this space and how have you been working on it?

M: This space is not yet defined, it's still a proposition to be tested. I feel that, although it came up strongly in the two residencies, it still is an open idea that we have to test. But the idea came from thinking about how this dance could have a stripe covering it. A stripe as in some kind of censoring, but also a bandage, a band-aid in space, something that creates impossibilities or that covers up in order to protect.

I have been working for quite a while with the idea of masks, which are a constant in my work and that I feel coming around again. I am following a flow that dates back to 2006 with Bull Dancing, which is about masking. Masking to nullify one's identity but also to de-hierarchize the body, shift the focus from/about the body, almost as to rotten the gaze of those watching. And I keep thinking about how this can happen without faces.

C: The stripe is also a very clear gesture towards the audience. How have you conceived the relationship with the viewer?

M: I'm always very concerned with the viewer and I can reach them in a more indirect, porous, less intellectual way. Closer to an experience. Since Suddenly Everywhere Is Black With People I have radically thought about the audience, taking them away from the situation of just sitting still and looking forward. Creating a space where they don’t need necessarily to participate, but experience something horizontally, as a happening that speaks to them directly. Now, I want to go back to the frontality, to a traditional stage with people sitting in the audience, with the lights out. This has been a challenge, making what happens on a traditional stage also be an experience.

C: Ever since I came in contact with your processes, the understanding of Affection has became very strong to me, not only as a work-tool, but also as a position. I wanted you to talk a little about that.

M: I think affection is an important word and a guide to my processes. But I feel that affection resides much more in a checkmate move than on a given thing. Exactly because of the need to create something, we go back to those people whose affection assures us they'll be together, despite all the turbulence that can happen during the process. Another word that is connected to sickness and symptom is contagion, and contamination is present in this process. I think of dance as Contamination. I think dance has this property that leaves a mark, that when it's strong, we can't forget it. Dance seems to be of this nature where something we saw 30 years ago still affects us. To me, having seen Pina Bausch dancing in 1980 in Rio de Janeiro is something that is still alive in me like a disease I caught, a virus I never shook off. So I feel dance has this power because it happens to the body, because it is physiological, hormonal. What we generate while dancing, and the way the viewer sees dance, has this characteristic of contagion. Being able to experience the contagion, to expose ourselves to the viruses out in the world, is an element in the creation of this piece and something that very much interests me.